|

|

||||

| Home

Society & Culture Traditional

Cultures

'Spirit of India' Jews

of India Technology Feature Technology

Investments

Films

|

|

|

||

|

the-south-asian.com March 2001 |

||||

|

Page 3 of 6

Raphael Meyer

The People At the community's peak in the 1940's there were

approximately 2,500 Jews in the state of Kerala-in Ernakulum, Parur,

Chennamangalam and Mala, all near Cochin City-and 300 in Jew Town. Today,

few of the country's remaining 5,500 Jews live in Cochin - 22, to be

exact-and many predict that the predominantly elderly community will be gone

within 25 years. Those who stayed behind were the wealthiest; they did

not want to risk losing their fortunes in the move and are today left with

the burden of sustaining the community. The Cochin Jews were historically divided into two major

communities-the so- called Black Jews, or Malabaris (85 percent of Cochinis),

who regard themselves as the descendants of the original settlers, and the

White Jews, or Paradesim (14 percent), descendants of immigrants from

various Middle East and European countries. There are also a few Brown Jews,

or Meshuhurarum, who are descended from emancipated slaves. They became

spice merchants, business owners and professionals and spoke the local

language -Malayalam-as well as English. The community has never had a rabbi

of its own and was rarely visited by one. Any synagogue elder is eligible to

lead prayers, and the men take turns. Although Jews, like Christians, are outside India's caste

system, they developed a strict code of their own, which for centuries

dictated that the three communities and their subgroups could not live

together, socialize or intermarry. The divisions between Jews began to break

down after 1948, when large scale emigration forced everyone together. The

majority of Jewish marriages are still arranged; married couples and their

children live with the husband's parents. Jewish women now wear bindis, the

small marks in the middle of their foreheads that at one time signified a

woman's marital status but are now merely a fashion statement. Perhaps the most unique aspect of the Indian Jewish

experience is the complete absence of discrimination by a host majority. The

secret of India's tolerance is the Hindu belief which confers legitimacy on

a wide diversity of cultural and religious groups even as it forbids

movement from one group to another. Entering Jew Town Road where it intersects with Jew Cemetery

Road is like entering another world. Merchants call out from open-air shops,

men squat in doorways or congregate in the middle of the street to smoke

their pipes and gossip, friendly and curious children follow visitors,

chattering endlessly, and three wheeled motorized taxis and bicycles thread

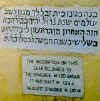

their way through the scene. Anchoring one end of Jew Town, at the end of Jew Cemetery

Road, is the Jewish burial place, with stone sepulchers aboveground and

inscriptions in Hebrew and Malayalam. From there, a walk through several

blocks will bring you to the Magen David decorated, wrought-iron gates of

the Paradesi synagogue. Along the way one can identify buildings that once

housed synagogues and prayer halls-as well as Jewish homes and

storefronts-by the still-visible stars and Hebrew inscriptions and

decorations. Built on land given the Cranganore exiles by the Raja and reconstructed after the Portuguese bombardment in 1662, the Paradesi is the oldest surviving synagogue in the former British Empire. White-walled and tile-roofed, with an inner courtyard lined with ancient Hebrew-inscribed gravestones, it was embellished in the mid eighteenth century by Ezekiel Rahabi, the Dutch East India Company's principal merchant and diplomat in Malabar, who built a Dutch-style clock tower with three faces: Hebrew numerals facing the synagogue, Roman numerals facing the palace and Indian numerals facing the harbor. Rahabi also had the floor paved with hand painted porcelain tiles, each with a different weeping willow pattern, brought from Canton.The synagogue shares a wall with the Raja's temple. According to a congregant, "While worshipping in the synagogue, we often hear their music and prayers, and they can hear us, too." L-R: the interior of the tiled pardesi synagogue with crystal chandeliers; the silver Torah scroll; the Tabernacle; the pulpit.The synagogue also contains silver- and gold decorated Torah scrolls; an Oriental carpet in front of the Ark (a gift from Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie), two brass columns commemorating pillars that stood in the Temple, two bimot (one in the women's section, a feature unique to the Jews of Kerala) and Torah crowns of solid gold set with gems given to the Cochini Jews by neighboring Rajas. The most striking feature, however, is the forest of lights hanging from the ceiling-silver, brass and glass oil-burning lamps and Belgian crystal chandeliers. In addition, the Paradesi houses 10 paintings which depict the history of the Jews of Kerala, as well as the 1,600-year-old copper plates-deposited in an iron box called a pandeal and carefully guarded by the elders - which are shown to visitors on request.

The Thekumbagum and the Kadavumbagham synagogues the temple complex is open to all Hindus. According to a congregant, "While worshipping in the synagogue, we often hear their music and prayers, and they can hear us, too."

|

||||

| Copyright © 2000 [the-south-asian.com]. Intellectual Property. All rights reserved. | ||||

| Home |