|

|

the-south-asian.com August 2007 |

|

|||

|

Famous

Bazaars

Ratan Tata Remaining articles

Books Between

Heaven and Hell

|

|

||||

|

Page

1 of 2

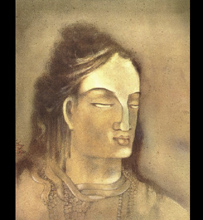

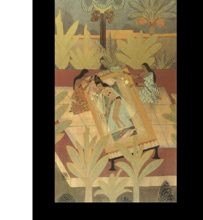

Nandalal Bose - a leading citizen of folk aristocracy By Dinkar Kowshik Master-mashai, as Nandalal Bose was fondly known, remains with us as a legend. His respect for nature was as profound as his reverence for the classics. Today he comes back to us as a living presence through his great achievement in art. Nandalal preferred to speak with forms. He wrote letters in sketches, he greeted with pictures, he blessed with drawings. Visual form was his life-breath.Nandlal appears like a culmination and fruition of an era. In him we witness the simplicity of an Indian peasant, the authenticity of an idealist and an enlightened patriot of the Gandhian school. His work shed the romantic verbiage and illustrative trappings of his contemporaries and developed along a definite path of formal synthesis. His swadeshi fervour did not make him illustrate the episodes of the national movement as visual reportage. He always forced the story to crystallise in a design almost like a unit form and there he expended his best talents of calligraphy and colour purely in terms of the aesthetics of vision. His swadeshi spirit was genuine, born of the soil. His respect for local material was real. Handmade paper, earth colours and handmade brushes were an outcome of his sense of sturdy self-reliance. He laughed at the consignments of British paper and colours. In truth, Nandlal, in his response to Gandhi Jiís call, had made a serious heart-searching and had reached back to the original current of Indian tradition.

Nandlalís early work in wash was extremely competent. It was delicate and yet sturdily constructed. He accepted the technique as was exemplified by Acharya Abanindranath Tagore. But he relied more on the structural emphasis than on the atmospheric ethereality. His line had a sinuous musculature and the colour tended towards symbolism. Visual play of light and shade did not in the least engage his interest. His study of Ajanta brought him face to face with a robust phase of realism. He at once recognised in those murals as archetype of Indian womanhood. The Ajanta woman is heavy Ė "like a mango tree laden with fruit." Her skin has the glow and lustre of a Lodhra flower. Her lower lip is heavy, sensuous, like a Bimba fruit. Her glances are like "lightning". She is, in sum, "desire" personified. Ajanta has used areas of dark colour and light colour and never attempted surface light and shade. Nandalal built his art on such sound foundations. His competence in wash painting never let him run away with the passing, evanescent effects of sunset glows or aging human beings in the dusk. The romanticism of Arabian Nights or Omar Khayyam series of Abanindranath gave Nandalal a starting point for his fresh experiments. He squarely based his efforts on the definite technique of tempera. He worked his own style enriched by his intimate experience of Ajanta, Jain, Rajput and Mughal art. His respect for his craft and profession was profound. This led him to accept the message of swadeshi in its practical aspect.

|

|||||

|

Copyright © 2000 - 2007 [the-south-asian.com]. Intellectual Property. All rights reserved. |

|||||