|

|

The South

Asian Life & Times - SALT |

|

|||

|

Contents Cover Story

Dr

Karan Singh's

59th National Film

'Rang'

Colors of

Mike Pandey wins

SaMaPa Music

|

|

||||

|

Rabindranath Tagore’s Art

A question that has baffled many critics is why did

Rabindranath start painting so late in life? Why not earlier? He did make

tentative beginnings in his early youth. But the prevailing Victorian taste

made him aware that any valid progress in this direction could only be made

through systematic training in copying from nature and long practice. At the

time, art schools taught students to copy from masters. But his inner being

resisted and avoided all imposed discipline. In a letter to Sir Jagdish Bose

(commonly quoted), he wrote that he was trying to woo the painter's muse and

was drawing with great patience, but added, with a certain sense of

amusement, that instead of the pencil he has been forced to use an eraser

much oftener. He goes on to say that he still cares for his drawings like a

mother who loves her handicapped child a little more than the others. In Rabindanath’s early manuscript `Malati Puthi' or

'Pocket Book', a manuscript so called because it was used for casual

scribbling of stray poems, doodling, and jotting expenses. one comes across

some of his early attempts at drawing, casual, amateurish and without much

promise. But even here, on one of the pages of the 'Pocket Book', one comes

across exceptional sketches like two heads of birds—long-beaked, drawn with

a dark crayon-pencil. The sketches have an inner vitality, coming not from

mere observation but out of an inner élan. Barring these stray examples, he

did not settle down to serious painting then.

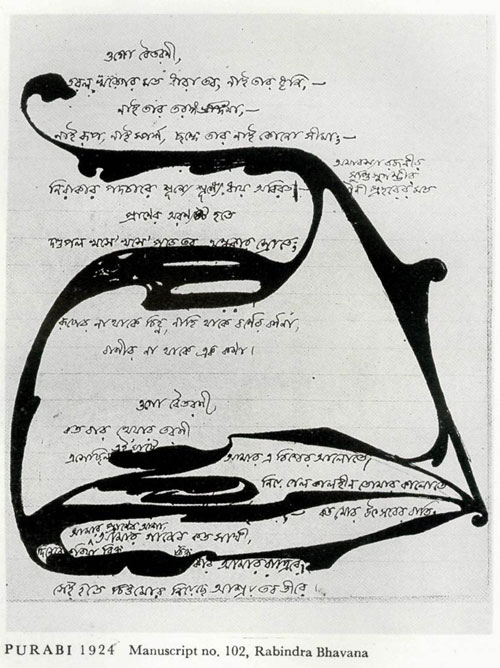

His European sojourns during the closing years of the nineteenth

century brought him into contact with the art movements of the time - Morris

and Art Nouveau. One can see the hangover of this movement in the flourish

of his signatures, both in Bengali and in English, where he let his hand

move in suave calligraphy. His handwriting was beautifully formed, large and

clear; and he always showed an instinctive taste in matters of spacing and

paragraphing his written text. Even while cancelling a date at the end of a

poem he used a flourish with an elegant Art Nouveau echo. This can be seen

in the manuscript of ‘Kheya’. In the same manuscript, the poem `Vidhir

bandhan katbe tumi' is knit together with a creeper-like line joining all

the crossed out words, ending in leaves and buds. This was in 1904.

|

|||||

|

Copyright © 2000 - 2012 [the-south-asian.com]. Intellectual Property. All rights reserved. |

|||||